I. How to Use

When to Use

-

Patients with syncope.

-

Patients receiving multiple QT-prolonging medicines.

Why Use

-

A prolonged QT interval is associated with an increased risk of torsade de pointes.

-

The QT shortens at faster heart rates; this calculator corrects the QT to the QT at a heart rate of 60.

-

The QT lengthens at slower heart rates; this calculator corrects the QT to the QT at a heart rate of 60.

II. Next Steps

Advice

Make sure that the QT interval measurement did not mistakenly include a U wave. If so, redo the measurement and calculations, and consider the etiologies for U wave.

If there is no U wave, consider common etiologies for prolonged QT interval, including:

-

Electrolyte abnormalities

-

Intrinsic cardiac causes

-

Central causes

-

Medications

If a short QT interval is observed, ensure measurement accuracy and consider short QT syndrome (see “Facts & Figures”).

Management

Subsequent management depends entirely on the etiology of the prolonged (or, rarer, shortened) QT interval. In general, however, the use of QT-prolonging medications in patients with QT prolongation should be minimized and only given after a thorough risk-and-benefit assessment.

III. Evidence

Evidence Appraisal

QT correction formulae were derived to correct for the inverse correlation between QT interval and heart rate. The most common formula used – and taught in medical schools – is the Bazett formula. Though commonly linked to a paper by Dr HC Bazett in 1920, that very paper only adapted the 1891 equations by Dr AD Waller to the QT interval. This formula was derived empirically (with little details given for the mathematical methodologies) and essentially defined the ideal QT interval for any individual for a given heart rate. This formed the basis of the modern Bazett formula, which was first mentioned by Drs Taran and Szilagyi in a paper in 1947.

Meanwhile, the lesser-known Fridericia, Hodges, Framingham, and Rautaharju formulae were successively derived over a span of 94 years, with the Fridericia formula being the oldest (1920) and the Rautaharju formula (2014) being the newest. Most of these formulae were derived using regression-based methods.

Subsequently, there has been constant debate on the ideal formula for QT interval correction. While some researchers have validated the Bazett formula in specific conditions, such as Dahlberg et al in patients with long QT syndrome, most studies have demonstrated the superiority of other formulae over the Bazett formula in terms of the ability to adjust for heart rate dependency and predict mortality, such as those by Patel et al (in a cohort of patients without atrial fibrillation), Tian et al (in a cohort of Chinese patients without cardiovascular disease), and Vandenberk et al (in a cohort of adult hospital attendees, and, separately, in a retrospective cohort of adult patients). In most studies, Bazett was consistently found to over-correct QT interval at higher heart rates and under-correct at lower heart rates, with the potential of drastically over-diagnosing QT prolongation (e.g. in studies by Vandenberk et al and Luo et al). For similar reasons, others have recommended against using the Bazett formula to diagnose short QT syndrome. However, there has also been at least 1 report suggesting Bazett to be superior in terms of predicting cardiac mortality, and another showing that the Bazett formula has better adjustment consistency than other formulae in infants and young children.

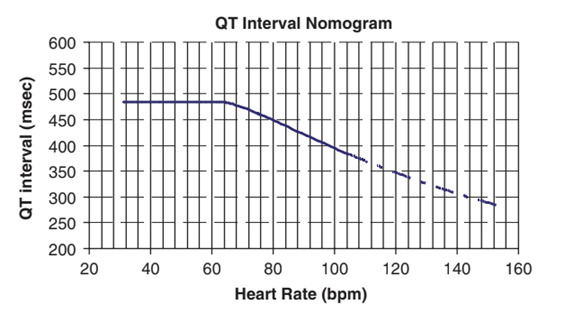

Of note, two scenarios have been investigated especially frequently. The first scenario is for the monitoring of drug-induced QT prolongation for stratifying the risk of torsades de pointes, for which a QT nomogram has been constructed. The same study also demonstrated the utility of the Bazett-corrected QT interval in identifying those at risk of drug-induced torsdaes de pointes. Others have shown that both the Bazett and Fredericia formulae (but not the Hodges or Framingham formulae) may interfere with such monitoring of QT interval, and that the Rautaharju formula may perform as well as or better than the aforementioned nomogram for predicting drug-induced torsades de pointes. The second scenario is for QT interval monitoring in athletes and young people, for which the underlying evidence has been summarized by Mahendran et al in a 2023 systematic review, which found that no study supported the use of the Bazett formula in these individuals, and that alternative formulae, especially the Fredericia formula, may be superior and preferable to the Bazett formula in these individuals.

Overall, there remains no clear consensus on the best / ideal method of correcting the QT interval for heart rate. Although a 2013 expert consensus of the Heart Rhythm Society, European Heart Rhythm Association, and the Asia Pacific Heart Rhythm Society relied on the Bazett formula for the diagnosis of long QT syndrome, the newer 2022 European arrhythmia guidelines recommended a specific correction formula. The aforementioned expert consensus also warned that QTc “should be calculated avoiding tachycardia and bradycardia to prevent the use of the Bazett formula at rates in which its correction is not linear and may lead to underestimation or overestimation of QTc values”. While the Bazett formula is likely to remain popular due to its simplicity and years of widespread dissemination, clinicians should be informed of the potential shortcomings of the Bazett formula and the overall uncertainties with the performance of different formulae.

Formula

RR interval = 60 / HR

Bazett Formula: QTc = QT interval / √ (RR interval)

Fridericia Formula: QTc = QT interval / (RR interval)1/3

Framingham Formula: QTc = QT interval + 154 x (1 - RR interval)

Hodges Formula: QTc = QT interval + 1.75 x [(60 / RR interval) − 60]

Rautaharju Formula: QTc = QT interval x (120 + HR) / 180

Facts & Figures

The 2022 ESC guidelines recommended a cutoff of QTc ≥480 ms (regardless of symptom) or LQTS diagnostic score >3, or ≥460 ms (individuals with an arrhythmic syncope without secondary causes for QT prolongation) for the diagnosis of long QT syndrome (including acquired long QT syndrome). Meanwhile, a 2013 expert consensus of the Heart Rhythm Society, European Heart Rhythm Association, and the Asia Pacific Heart Rhythm Society recommended the following diagnostic criteria for long QT syndrome:

-

Long QT syndrome is diagnosed:

-

In the presence of an LQTS risk score > 3.5 in the absence of a secondary cause for QT prolongation, and/or

-

In the presence of an unequivocally pathogenic mutation in one of the LQTS genes, or

-

In the presence of a QTc> 500 ms in repeated 12-lead ECG and in the absence of a secondary

-

cause for QT prolongation.

-

-

Long QT syndrome can be diagnosed in the presence of a QTc between 480-499 ms in repeated 12-lead ECGs in a patient with unexplained syncope in the absence of a secondary cause for QT prolongation and in the absence of a pathogenic mutation.

A longer QTc puts the patient at increased risk for torsade de pointes. A QTc of >500 ms indicates especially high risk of torsade de pointes.

Some causes of prolonged QT:

-

Electrolyte abnormalities

-

Hypocalcemia

-

Hypokalemia

-

Hypomagnesemia

-

-

Intrinsic cardiac causes

-

Myocardial ischemia

-

After cardiac arrest

-

CAD

-

Cardiomyopathy

-

Severe bradycardia, high-grade AV block

-

Congenital long QT syndrome

-

-

Central causes

-

Raised intracranial pressure

-

Autonomic dysfunction

-

Hypothyroid

-

Hypothermia

-

-

Medications

-

Anti-arrhythmics

-

Psychotropic drugs

-

Other drugs

-

QT Nomogram for evaluation of patients at high risk of torsades de pointes – the QT interval here is the absolute / uncorrected QT interval. Patients with parameters plotted above the line are at high risk of torsades de pointes:

In the rarer case of a short QT interval, the 2022 European guidelines recommended that short QT syndrome be diagnosed in the presence of QTc ≤360 ms and one of more of the following: (a) a pathogenic mutation, (b) a family history of short QT syndrome, (c) survival from a ventricular tachycardia or fibrillation episode in the absence of heart disease. The same guidelines recommended short QT syndrome to be considered in the presence of a QTc ≤320 ms, and in the presence of a QTc between 320 and 360 ms with arrhythmic syncope and a family history of sudden death at age <40 years. Meanwhile, the aforementioned 2013 expert consensus recommended the following diagnostic criteria for short QT syndrome:

-

Short QT syndrome is diagnosed in the presence of a QTc < 330 ms.

-

Short QT syndrome can be diagnosed in the presence of a QTc < 360 ms and one or more of the following: a pathogenic mutation, family history of SQTS, family history of sudden death at age <40, survival of a VT/VF episode in the absence of heart disease.

Literature

Original/Primary

Taran LM, Szilagyi N. The duration of the electrical systole, Q-T, in acute rheumatic carditis in children. Am Heart J. 1947 Jan;33(1):14-26. doi: 10.1016/0002-8703(47)90421-3.

Bazett HC. “An analysis of the time-relations of electrocardiograms”. Heart 1920; 7: 353–370.

Fridericia LS. The duration of systole in an electrocardiogram in normal humans and in patients with heart disease. Acta Medica Scandinavica. 1920;53:469-4861.

Hodges MS, Salerno D, Erlinen D. Bazett’s QT correction reviewed: evidence that a linear QT correction for heart rate is better. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1983;1:694.

Sagie A, Larson MG, Goldberg RJ, Bengston JR, Levy D. An improved method for adjusting the QT interval for heart rate (the Framingham Heart Study) The American Journal of Cardiology 1992; 70; 797-801.

Rautaharju PM, Mason JW, Akiyama T. New age- and sex-specific criteria for QT prolongation based on rate correction formulas that minimize bias at the upper normal limits. Int J Cardiol. 2014;174(3):535-540.

Validation and Additional Studies

Patel PJ, Borovskiy Y, Killian A, Verdino RJ, Epstein AE, Callans DJ, Marchlinski FE, Deo R. Optimal QT interval correction formula in sinus tachycardia for identifying cardiovascular and mortality risk: Findings from the Penn Atrial Fibrillation Free study. Heart Rhythm. 2016 Feb;13(2):527-35. doi: 10.1016/j.hrthm.2015.11.008.

Tian WB, Zhang WS, Jiang CQ, Liu XY, Zhu F, Jin YL, Zhu T, Lam TH, Cheng KK, Xu L. Optimal QT Correction Formula for Older Chinese: Guangzhou Biobank Cohort Study. Cardiology. 2024 Oct 30:1-12. doi: 10.1159/000542238.

Yazdanpanah MH, Naghizadeh MM, Sayyadipoor S, Farjam M. The best QT correction formula in a non-hospitalized population: the Fasa PERSIAN cohort study. BMC Cardiovasc Disord. 2022 Feb 16;22(1):52. doi: 10.1186/s12872-022-02502-2.

Dahlberg P, Diamant UB, Gilljam T, Rydberg A, Bergfeldt L. QT correction using Bazett’s formula remains preferable in long QT syndrome type 1 and 2. Ann Noninvasive Electrocardiol. 2021 Jan;26(1):e12804. doi: 10.1111/anec.12804.

Mahendran S, Gupta I, Davis J, Davis AJ, Orchard JW, Orchard JJ. Comparison of methods for correcting QT interval in athletes and young people: A systematic review. Clin Cardiol. 2023 Sep;46(9):1106-1115. doi: 10.1002/clc.24093.

Vandenberk B, Vandael E, Robyns T, et al. Which QT Correction Formulae to Use for QT Monitoring?. J Am Heart Assoc. 2016;5(6).

Extramiana F, Maury P, Maison-Blanche P, Duparc A, Delay M, Leenhardt A. Electrocardiographic biomarkers of ventricular repolarisation in a single family of short QT syndrome and the role of the Bazett correction formula. Am J Cardiol. 2008 Mar 15;101(6):855-60. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2007.10.049.

Vandenberk B, Vandael E, Robyns T, Vandenberghe J, Garweg C, Foulon V, Ector J, Willems R. QT correction across the heart rate spectrum, in atrial fibrillation and ventricular conduction defects. Pacing Clin Electrophysiol. 2018 Sep;41(9):1101-1108. doi: 10.1111/pace.13423.

Phan DQ, Silka MJ, Lan YT, Chang RK. Comparison of formulas for calculation of the corrected QT interval in infants and young children. J Pediatr. 2015 Apr;166(4):960-4.e1-2. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2014.12.037.

Chan A, Isbister GK, Kirkpatrick CMJ, Dufful SB. Drug-induced QT prolongation and torsades de pointes: evaluation of a QT nomogram. QJM. 2007;100(10):609-615.

Othong R, Wattanasansomboon S, Kruutsaha T, Chesson D, Arj-Ong Vallibhakara S, Kazzi Z. Utility of QT interval corrected by Rautaharju method to predict drug-induced torsade de pointes. Clin Toxicol (Phila). 2019;57(4):234-239.

Indik JH, Pearson EC, Fried K, Woosley RL. Bazett and Fridericia QT correction formulas interfere with measurement of drug-induced changes in QT interval. Heart Rhythm. 2006 Sep;3(9):1003-7. doi: 10.1016/j.hrthm.2006.05.023.

Luo S, Michler K, Johnston P, Macfarlane PW. A comparison of commonly used QT correction formulae: the effect of heart rate on the QTc of normal ECGs. J Electrocardiol. 2004;37 Suppl:81-90. doi: 10.1016/j.jelectrocard.2004.08.030.

Guidelines

Zeppenfeld K, Tfelt-Hansen J, de Riva M, Winkel BG, Behr ER, Blom NA, Charron P, Corrado D, Dagres N, de Chillou C, Eckardt L, Friede T, Haugaa KH, Hocini M, Lambiase PD, Marijon E, Merino JL, Peichl P, Priori SG, Reichlin T, Schulz-Menger J, Sticherling C, Tzeis S, Verstrael A, Volterrani M; ESC Scientific Document Group. 2022 ESC Guidelines for the management of patients with ventricular arrhythmias and the prevention of sudden cardiac death. Eur Heart J. 2022 Oct 21;43(40):3997-4126. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehac262.

Priori SG, Wilde AA, Horie M, Cho Y, Behr ER, Berul C, Blom N, Brugada J, Chiang CE, Huikuri H, Kannankeril P, Krahn A, Leenhardt A, Moss A, Schwartz PJ, Shimizu W, Tomaselli G, Tracy C. HRS/EHRA/APHRS expert consensus statement on the diagnosis and management of patients with inherited primary arrhythmia syndromes: document endorsed by HRS, EHRA, and APHRS in May 2013 and by ACCF, AHA, PACES, and AEPC in June 2013. Heart Rhythm. 2013 Dec;10(12):1932-63. doi: 10.1016/j.hrthm.2013.05.014.

Other Studies

Cobos Gil MA, García Rubira JC. Who was the creator of Bazett’s formula? Rev Esp Cardiol. 2008 Aug;61(8):896-7.